Overview of the Etruscans

Ancient Italy is of course confounded with Rome, but at some point, as the saying goes "Rome was not built on a day". At the time the Urbs was no more than a small backwater with walls and a forum right in the middle of hilly hamlets, Italy was ruled by Empires and confederations: To the south, the Oscan confederation and the city states of "great greece" or Magna Grecia, Taras and others. To the center and axis of the boot, the Samnite confederations, four powerful tribes of hardy mountaineers that would beat back the Romans until 298 BC and made the life of the Campanians miserable. To the north-west, the powerful Etruscan Empire, which at some point, went to take ancient Rome and made it an Etruscan city-state.

Lars Porsenna and his followers (Richard Hook)

Of this, a serie of seven semi-mythical Etruscan kings and the last portayed as an egotistical tyran, Tarquinus Superbus. Kicked off by Brutus, leading other Roman nobles, the revolution that followed saw Rome becoming a Republic, with a complicated power system of checks and balance, two yearly consuls, the senate and populare tribunes, about 700 BC. Tarquinus tried to retake the city, found powerul allies, but failed, partly due to the heroic last stand of Horatius on Milvius bridge.

From then on, Rome became a newly independent city-state, and the city has been much improved since Etruscan times, while the army still retained many Etruscan characteristics. This was not going to last, thanks to the Samnite wars. But that's a story for another day. Let's have a look on the Etruscan army, which ruled most of the peninsula, fought and traded with the Celts, Carthaginians and Greeks. At first glance, the Etruscan Empire seemed elongated from the Alps to Campania on a long coastal western band. But Celtic pressure to the north drove out the Etruscans from the fertile Po valley, where only small villages remained in what is today current Emilia-Romagna, south-eastern Lombardy and southern Veneto. Since there was no geographical protection here, we can assume than around 700 BC, the Etruscans had passed a peace treaty with the Gauls, once the latter had settled. By 700 BC indeed, it's not yet the golden age of the "Tuscan civilization" which gave ud the Tuscany region. Etruscans city-states were found south of the Arno river, western Umbria, northern and central Lazio, and at the greatest expansion around 500 BC, down south to some areas of Campania.

From then on, Rome became a newly independent city-state, and the city has been much improved since Etruscan times, while the army still retained many Etruscan characteristics. This was not going to last, thanks to the Samnite wars. But that's a story for another day. Let's have a look on the Etruscan army, which ruled most of the peninsula, fought and traded with the Celts, Carthaginians and Greeks. At first glance, the Etruscan Empire seemed elongated from the Alps to Campania on a long coastal western band. But Celtic pressure to the north drove out the Etruscans from the fertile Po valley, where only small villages remained in what is today current Emilia-Romagna, south-eastern Lombardy and southern Veneto. Since there was no geographical protection here, we can assume than around 700 BC, the Etruscans had passed a peace treaty with the Gauls, once the latter had settled. By 700 BC indeed, it's not yet the golden age of the "Tuscan civilization" which gave ud the Tuscany region. Etruscans city-states were found south of the Arno river, western Umbria, northern and central Lazio, and at the greatest expansion around 500 BC, down south to some areas of Campania.

Whereas the situation of Western Etruscans was quite good, with dynamic trade with the Carthaginians and Massilia, flourishing art and rich city-states that can afford a lavishly living upper class (in start contrast to the austere Romans), to the north, there was little hope of any expansion. The Western confederation of the Ligurians as well as the Eastern Venetians were die-hard ancient inhabitants of these lands since the bronze age, and considered "barbarians", only distinguished from northern Italy gauls by wearing a tunic rather than braccae, or trousers. A mountain rift divided these lands to the west from their eastern neighbours, the Umbrian and Sabines. Mountains also protected the Etruscans from further northern incursions. But it was a civilization schock, and illutrators such as Mc bride, Giuseppe Rava and others dramaticized the "Keltoi Tromos", the Celtic terror as typical barbarians pitted against greek-like hoplites in frozen mountain passes.

About Etruscan warfare

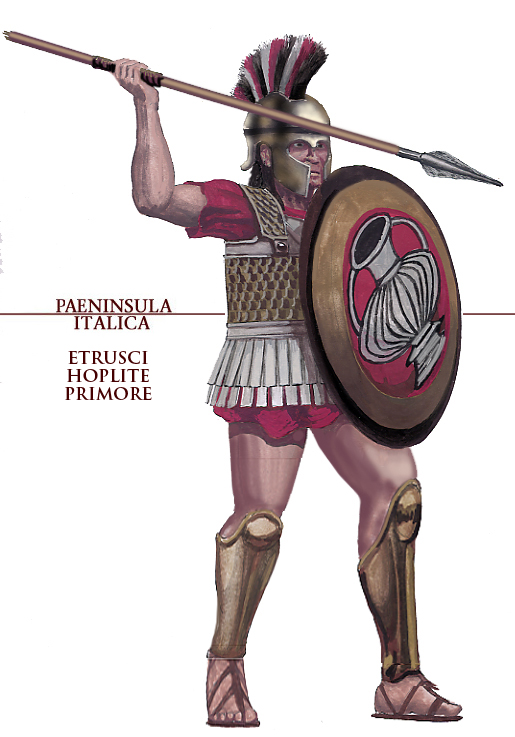

There is a lot to say about Etruscan civilization, although it's off-topic. It was brillant, free, and by many aspects recalled the Greeks, but with very specific traits. It's no wonder why Greek warfare was adopted, with local variants, although the Etruscans developed about 900 BCE (Iron Age Villanovan culture). While themselves called their culture originated from Rasna, the classic Greeks called them Tyrrhenians, and an association was made by a few authors with the Teresh (Sea Peoples), but it's wildly contested. Etruscans had no original texts of religion or philosophy, therefore most evidences were found in tombs. In almost none of them were found depiction of ancient Etruscan warriors. Nowodays studies showed this people was autochthonous in central Italy however, and it's well possible that its culture was influenced by Halstatt culture too. Before the bronze sword became more popular with elites, the typical villanovian warrior had a conical helmet, a spear and javelins, a dagger, and an axe. Much later, probably under Greek influence in the south appeared the classical hoplite (pic).

There is a lot to say about Etruscan civilization, although it's off-topic. It was brillant, free, and by many aspects recalled the Greeks, but with very specific traits. It's no wonder why Greek warfare was adopted, with local variants, although the Etruscans developed about 900 BCE (Iron Age Villanovan culture). While themselves called their culture originated from Rasna, the classic Greeks called them Tyrrhenians, and an association was made by a few authors with the Teresh (Sea Peoples), but it's wildly contested. Etruscans had no original texts of religion or philosophy, therefore most evidences were found in tombs. In almost none of them were found depiction of ancient Etruscan warriors. Nowodays studies showed this people was autochthonous in central Italy however, and it's well possible that its culture was influenced by Halstatt culture too. Before the bronze sword became more popular with elites, the typical villanovian warrior had a conical helmet, a spear and javelins, a dagger, and an axe. Much later, probably under Greek influence in the south appeared the classical hoplite (pic).

In addition to a round shield, a thorax plate and a typical pot helmet with a metal crest seemed to have been the rule, while noble warriors tend to have a fully metallic "plastron" or bust protection which was lighter than the classic breastplate, and were found. The scutum made also its apparition. This gear was close to the one Venetians and Ligurian used, as well as early Celts. There is one Candelabrum bronze statuette from Vetulonia (now Florence) showing a warrior with an aspis-like shield with circles as decoration, more robust than the famous Etruscan parade shield (Circolo del tritone), strapped on his back. He is wielding a mace and his helmet is of the familiar old calotte "crested style", similar to the Ligurians. The 20 cm pectoral breastplate was rectangular and about 20 cm with recurving sides.

Etruscan league:

Being city-states, the Etruscan leagues would have mastered the same kind of levied citizen army, wit similar composition to the Greeks, and few differences. The middle class typically provided hoplites with the typical panoply, while the lower-class citizen were armed with simple spears/javelins and mass-produced scutum, and no protection. Peasants of the surrounding countryside provided the light infantry, young javelinmen, picked-up axemen, forester archers and shepherd slingers, plus scout cavalry. Little is known about Etruscan cavalry, less than infantry as almost no representation was ever found. We can assume however, by reference to the 300 Celeres of the early Roman-Etruscan army, that a noble medium to heavy cavalry core existed in each city, related to the highest echelons of the city-state and potentially only the largest of them, like Tarchuna.The Etruscans military tradition also provided considerable economic advantage to the civilization. Campaigns occurred during summer months, and small armies raided neighboring areas, making territorial gains, combating piracy and acquiring land, prestige, goods, and slaves. Ransom was also widespread. Prisoners could be sold to be sacrificed, honoring fallen leaders.

Left: An Etruscan securigeri or sciere of southern Etruria. These picked-up individuals used a two-handed axe and acted as line-breakers. Axemen were typical of the Etruscans, like heavy peltasts such as the Ensiferi and swordsmen cladded in heavy armour like hoplites. A collossal Etruscan terracota warrior standing over eight feet tall, fired in pieces and en the end too large for the room it was being modeled, but instead of the elegant classical proportions of genuine Etruscan sculpture, produced a stocky, disproportionate torso and troubled some scholars. It was purchased in 1921 by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, reconstructed from fragments by local experts. Warrior of the time, like many Etruscan statues, showed a partially nude warrior from the waist down. It was a well-made fake created by Riccardo Riccardi and Alfredo Fioravanti.

Left: An Etruscan securigeri or sciere of southern Etruria. These picked-up individuals used a two-handed axe and acted as line-breakers. Axemen were typical of the Etruscans, like heavy peltasts such as the Ensiferi and swordsmen cladded in heavy armour like hoplites. A collossal Etruscan terracota warrior standing over eight feet tall, fired in pieces and en the end too large for the room it was being modeled, but instead of the elegant classical proportions of genuine Etruscan sculpture, produced a stocky, disproportionate torso and troubled some scholars. It was purchased in 1921 by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, reconstructed from fragments by local experts. Warrior of the time, like many Etruscan statues, showed a partially nude warrior from the waist down. It was a well-made fake created by Riccardo Riccardi and Alfredo Fioravanti.

Right: an assortment of ancient warriors (author unknown); from the first plan: Etruscan hoplite warrior, Oscan warrior, and Venetian. Note for the latter it was a bronze "disc and studs" patterned-style helmet. The central figure is a known depiction with a large rim pot helmet and large scutum, two javelins and longshield.

Right: an assortment of ancient warriors (author unknown); from the first plan: Etruscan hoplite warrior, Oscan warrior, and Venetian. Note for the latter it was a bronze "disc and studs" patterned-style helmet. The central figure is a known depiction with a large rim pot helmet and large scutum, two javelins and longshield.

CATW's etruscan hoplites, with the pot helmet and transverse crest.

There is a depiction of three possibly Etruscan hoplites on the lid of the Praestnestine Cist showing two warriors carryin the body of a third. They don"t show shields but have their rather short Xyston-like lances (about 2.20 m if the representaion is accurate) and crested halmets of the Chalcidian type with their cheek-guards up. Both are bearded and shows a composite armor rather than a muscle cuirass (4th Century BC).

Venetic fighting system (Richard Hook), comprising units that were seen also with Etruscan armies: Hoplite, levied spearman and axe-bearer.

In the usual Etruscan way of seeing their ongoing conflict they saw themselves as "Greeks" as opposed to the "Trojan" Romans, from the largely held, supported and believed assumption the Romans ancestors originated in Trojan settlers. The above representation is probably from the Certosa Situla (vase fragment) showing the four classes of infantry shared by early Roman armies and perhaps found also in Etruscan armies: Hoplites, medium infantry with almost square (but rounded) shields and metal helmets, long spears and light spearmen with a pair of javelins, ovale/oblong long Herzsprung-shaped shields, disk and stud helmets, and skirmishers.

Celts vs Etruscans in 500 BC, Pô valley (Angus Mc bride).

Wars with the Etruscans:

After Livy's depiction of the early days of the Roman "revolution", newly-found republic and the revenge of the last etruscan king, the first Roman-Etruscan war erupted in 483 BCE with Veii, barely five miles north of Rome. According to Livy there was an endless competition with Rome, with wars erupting yearly at the same season, like a neighbour contest. The war ended in 474 with a 40-years truce signed, probably motivated by the bigger scope of the war between Etruscans and Syracuse at that time. Most of the Etruscan Navy was destroyed by Hiero I.However war returned from 437 BC, provoked by Lars Tolumnius killing the Roman embassy. The Romans led a succesful siege to allied city of Fidenae, and took it, without intervention of the Etruscan league. This resulted in a new 30-year truce in 435 BC. Eventually the truce as cut short, the Romans led siege to Veii which fall after ten years, circa 396 BC.

Then, the Romans fought with Tarquinii from 358 to 351 BC, the only major Etruscan city after Veii, but this time the city-state was supported by Falerii and Caere. All three citiies would ultimately sign a truce, whereas no support came from the league, again, perhaps too focused on the Greeks from Syracuse.

The last war wth Rome erupted in 311 BC with city-states such as Cortona, Sutrium, Clusium and Arretium raided the newly-held territory by Rome around Sutrium. Perusia, Cortona, Arretium, and Volsinii eventually sued for peace; but soon the Samnite wars make resurface the northern Etruscan threat by the will of Gellius Egnatus to seek a larger alliance. The war dragged on until 293 BC with a total defeat for the coalition, but the Etruscans were certainly not done yet.

The four infantry types of the Etrurian army: Left to right the Hoplite, longshield spearmen, shortshield spearmen (both with sword and probably classed by ages and resources like the Roman principes and Hastati), and levied spearmen/javelinmen (src. unknown).

The next years are rather foggy, but the Etruscans allied with Gauls, won over the Romans in 284 BC but the coalition was definitely beaten ithe next year at Vadimon and by 280, seven major city-states were forced to join Rome's orbit. The final major Etruscan stronghold to fall was Caere in 273 BC. From then on the "Etruscans" are part of the Roman history at large. This allowed Rome to progress to the north with immense teritory gains and secured a large buffer zone with its victory over the Samnites to Campania, the south and Appenine mountains.

The "last Etruscans" of the Falerii rebelled in 241 BC but were crushed and the population sold to slavery. Meanwhile Rome has just jumped into the shoes of the former civilization, taking over trade, a merchant fleet and network, considerable resources and manpower, and a starting base to operate against the next enemies north of Italy, the Gauls. Also during the Etruscan-Roman wars, internal politics changed dramatically at Rome, with the Plebeians becoming a true political force. The occupation of Etruria was sufficiently soft and based on reciprocal benefits that in 218 BC when Hannibal came in the area, all city-states choosed to remain faithful to Rome.

Celts invading Etruscan territories in 400 BC, Pô valley (Angus Mc bride).

More images

Pic of a 508 BC Milvius bridge Etruscan hoplite (Mc bride)Etruscan Hoplite, spearman, slinger and Charioteer (U)

Early Etruscan warriors (Rava)

Etruscan king (Rava)

Early Thyrrenian warriors 750-500 BC (Rava)

Etruscan hoplites and officers 300 BC (Rava)

Celtic incursions in the Po valley (Mc bride)

Etruscan and other Italic warriors (U)

Etruscans vs Romans 500 BC (Rava)

Italic warriotrs 800-700 BC

Examples of helmet, classic, crested, and "chinese hat" type

Etruscan hoplites, by G. Rava. The rear one is showin a composite armor, lamellar bronze, the other (1) a bronze muscle cuirass and montefortino type helmet with Celtic cheeckgyards.

Late Etruscans, 3rd Century BC (G. Rava). This shows little influence of the celts at that stage.

Another hoplite example (unknown)

Etrusca warriors, one wielding an axe.

Etrusco-Tarquinian officers and Royal Romans

Sources/Read More

Osprey Publishing Etruscans - Raffaele D’Amato, Andrea Salimbeti, Giuseppe RavaEtruscan terracota warriors - Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Archaic hoplite

OSPREY Men-at-arms 283 Early Roman Armies - N. Sekunda, Northwood, Richard Hook.

B. D'Agostino, 'Military Organisation and Social Structure in Archaic Etruria' in O. Murray & S. Price (eds), The Greek City: From Homer to Alexander (Oxford 1990), 58-82

Peter Connolly, Greece and Rome at War (London, rev. ed. 2006), 91-100

Ross Cowan, Roman Conquests: Italy (Barnsley 2009)

Ross Cowan, 'The Art of the Etruscan Armourer' in Jean MacIntosh Turfa (ed.) The Etruscan World (London & New York 2013), 747-748

David George, 'Technology, Ideology, Warfare and the Etruscans Before the Roman Conquest' in Jean MacIntosh Turfa (ed.) The Etruscan World (London & New York 2013), 738-746

W.V. Harris, Rome in Etruria and Umbria (Oxford 1971)

L. Rawlings, 'Condottieri and Clansmen: Early Italian Raiding, Warfare and the State' in K. Hopwood (ed.), Organised Crime in Antiquity (Cardiff 1999), 97-127

P. Stary, 'Foreign Elements in Etruscan Arms and Armour: 8th to 3rd Centuries BC', Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 45 (1979), 179-206

Jean MacIntosh Turfa, Catalogue of the Etruscan Gallery of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (Philadelphia 2005)

Various authors, 'Warfare' in M. Torelli (ed.), The Etruscans (New York 2001), 558-565 Etruscan warrior panoplies found

ETRUSCAN WARFARE: ARMY ORGANIZATION, TACTICS AND OTHER MILITARY FEATURES by Periklis Deligiannis

3400 entries on Etruscan warfare on academia.edu

Etruscan Warfare on ancient.eu

On weaponsandwarfare.com

Amazing works of Angel Garcia Pinto

♕ Aquitani & Vasci ♕ Celts ♕ Indo-greeks ♕ Veneti ♕ Yuezhi ♕ Indians ♕ Etruscans ♕ Numidians ♕ Samnites ♕ Judaean ♕ Ancient Chinese ♕ Corsico-Sardinians

⚔ Cingetos ⚔ Immortals ⚔ Cavaros ⚔ Cataphract ⚔ Romphaiorioi ⚔ Chalkaspidai ⚔ Devotio Warrior ⚔ Scythian Horse archer ⚔ The Ambactos ⚔ Iberian warfare ⚔ Illyrian warriors ⚔ Germanic spearmen ⚔ Carthaginian Hoplite ⚔ Thracian Peltast ⚔ Caetrati ⚔ Ensiferi ⚔ Hippakontistai ⚔ Hastati ⚔ Gaesatae ⚔ Cretan Archer ⚔ Thorakitai ⚔ Soldurii ⚔ Iphikrates ⚔ Kardaka ⚔ The thureophoroi